Summary:

Persistent deficits and growing debt levels in developed markets highlight long-term risks and support globally diversified thinking.

As global debt levels climb and fiscal strategies evolve, investors are paying close attention to how policies like the “One Big Beautiful Bill” may influence long-term economic dynamics. This article offers a plain-language overview of the shifting fiscal landscape, the implications of persistent deficits, and why global diversification is more relevant than ever.

For deeper insights across equity, fixed income, and macro trends, read this quarter’s comprehensive market outlook.

Our Perspective:

As macro conditions soften due to a longer period of elevated rates, persistently high debt levels in the United States (US) and abroad may prompt investors to look elsewhere for safety from volatility.

Tax and Spend or Spend and Tax

The fiscal landscape in developed markets, particularly the US, is becoming increasingly complex. While debt has always played a role in sovereign finance, the current magnitude and structure of deficits in the post-COVID, post-Great Financial Crisis (GFC) world present long-term challenges that merit close attention. Policymakers continue to rely heavily on debt as a policy lever.

A current example is a major omnibus proposal in Washington—dubbed the “One Big Beautiful Bill”—which includes provisions to make Trump-era tax cuts permanent, expand deductions for research and development costs and business interest expenses, and reinstate full expensing of depreciable assets. These measures are designed to stimulate short-term investment but are estimated to add $2.4 to $3 trillion to the federal budget over the next decade. While aimed at boosting investment and economic growth, the bill further underscores a policy pattern of stimulus through borrowing.

The bill also expects to boost spending on defense, immigration enforcement, and infrastructure. Proposed offsets, such as reductions in Medicaid and food assistance, may soften the fiscal impact but are unpopular with several lawmakers on both sides of the aisle and unlikely to eliminate it. Coupled with a proposed $5 trillion debt ceiling increase, the bill reflects a continued reliance on deficit financing.

Mortgaging the Future

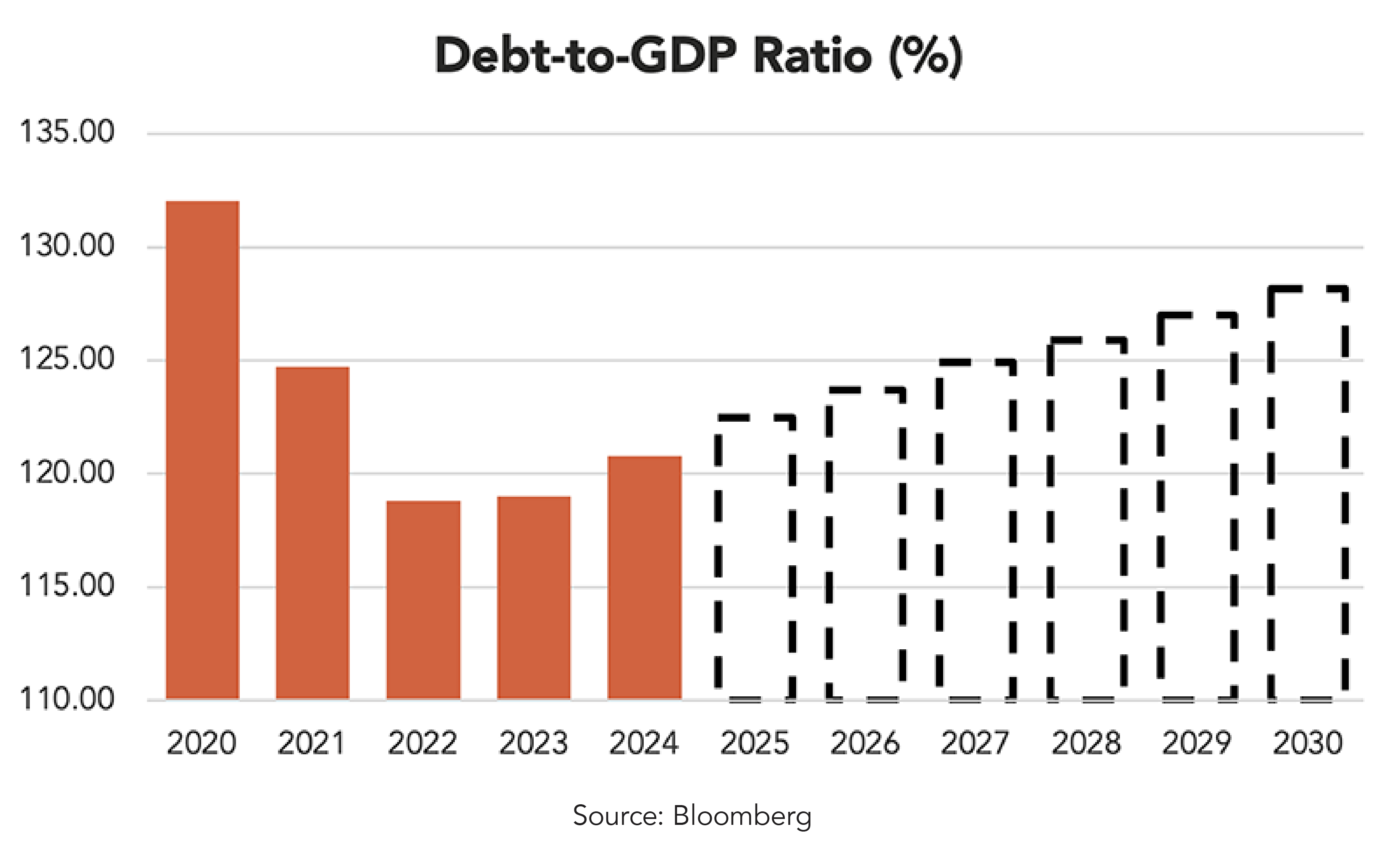

As the chart shows, the US debt-to-GDP ratio currently stands at approximately 120% and is projected to rise to 130% by 2030. This is set against the backdrop of ~2% long-term GDP growth expectations, as recently highlighted by the Federal Reserve. This would not present a long-term sustainability problem as long as economic growth and/or productivity outpace the deficit's growth rate. Put simply, debt is growing faster than the economy.

While the US continues to benefit from its status as the world’s reserve nation, supported by global demand for dollars for both trade settlement and investment, this advantage is ultimately rooted in trust and credibility. A sustained trend of rising debt could test that foundation over time.

Historically, deficits have been used strategically to stimulate the economy during downturns and invest in long-term economic growth. However, in recent decades, deficits have become more structural in nature. From the post-WW2 decline in debt levels, we transitioned through the GFC, the Eurozone Crisis of the early 2010s, and the COVID-19 pandemic into an environment where deficits are increasingly persistent.

To put this into perspective:

- During the Great Depression, US debt peaked at 80% of GDP.

- During WW2, it surged to 150% of GDP.

- After falling, debt rose sharply during the GFC and again during COVID.

Today, we manage peacetime deficits and debt levels without an acute crisis, suggesting a new regime. Though not cause for immediate alarm, it warrants thoughtful portfolio positioning.

Bond Market Pushback

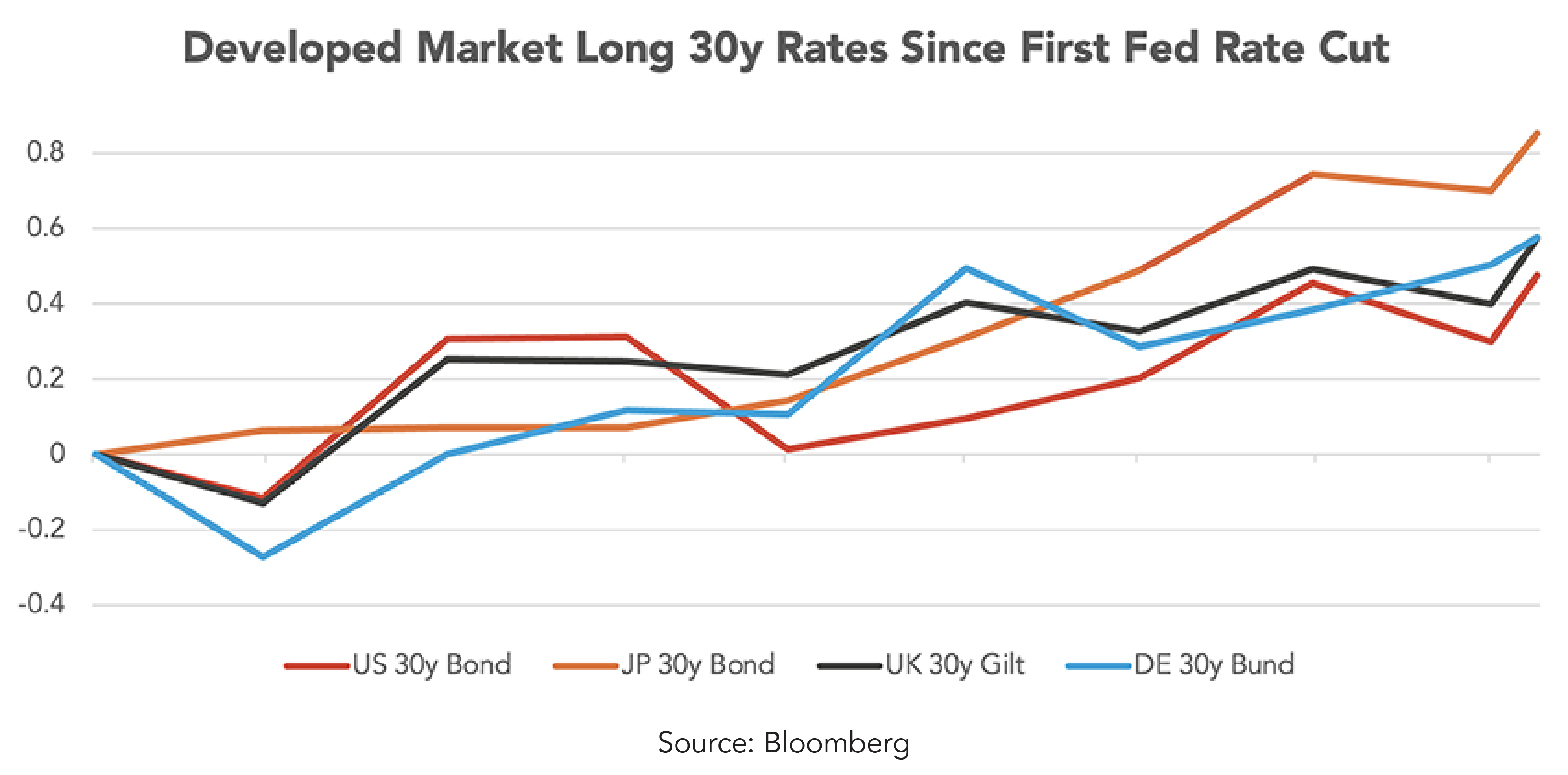

As the fiscal ambitions of developed nations expand, markets are beginning to show signs of resistance. While central banks in many developed economies have shifted toward easing, long-end yields are moving in the opposite direction. This divergence reflects a subtle but growing tension between monetary policy and fiscal behavior.

In recent months, 30-year government bond yields have risen even as central banks cut policy rates or signal dovish intentions. This trend has emerged across several developed markets, including:

- US: The Treasury curve has steepened due to concerns that continued deficit spending will keep the Treasury supply elevated.

- Germany: Bund yields have firmed despite a weak growth backdrop, mainly in response to constitutional debates over fiscal expansion.

- Japan: The Bank of Japan’s shift away from yield curve control has coincided with a rise in Japanese Government Bond yields, reflecting investor uncertainty over the fiscal trajectory.

- United Kingdom: The market’s adverse reaction to unfunded fiscal proposals in 2022 remains cautionary.

What’s happening here is more than a technical market adjustment—it’s a signal that credit markets are beginning to price in fiscal risk at the sovereign level. In effect, markets demand a higher risk premium for long-duration government debt in countries that rely heavily on borrowing without a clear path to debt consolidation.

This creates challenges for both policymakers and investors. For governments, rising yields increase debt servicing costs and complicate future stimulus efforts. For investors, it raises critical questions about how to position fixed income allocations traditionally viewed as conservative.

This macro backdrop opens the door to reconsidering where conservatively oriented capital might go, especially if the insular benefits of developed government bonds are somewhat diminished. The traditional paradigm that developed markets are inherently safer than emerging ones is evolving. By expanding their global opportunity set, investors may uncover greater relative value and more balanced risk profiles.

This is not a recommendation to exit developed market fixed income entirely. Rather, it’s a call to rethink what resilience looks like in a world where debt sustainability is no longer a given. Emerging market debt, particularly denominated in the local currency, may offer diversification benefits, return potential, and a hedge against fiscal drift in the developed world. This asset class is one potential option worth considering.

The article highlights how persistent deficits and rising sovereign debt levels are reshaping the macroeconomic landscape—both in the U.S. and abroad. As markets begin to demand higher premiums for long-term debt and traditional assumptions about safety are challenged, investors have an opportunity to reflect on what portfolio resilience means going forward.

Interested in learning more about how to position your portfolio amid shifting global dynamics? Connect with a Midland Wealth Advisor today.

.jpg?sfvrsn=3df2d46f_3)